How to do business in China

Peter Hardwick of the Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board travelled to China as part of a European trade delegation to promote agricultural exports.

Ni hao (that’s “hello” in Chinese) from Beijing. It’s 9am local time (2am back home) and, after a few hours jet-lagged sleep back at the hotel, I arrive bright and early at the British Embassy to discuss the agenda for tomorrow’s meeting.

The biggest challenge is how to respond to new Chinese legislation introduced in the wake of the melamine scandal in the dairy industry. The Chinese authorities have addressed food safety robustly at home and insist that all imports meet the same standards. The EU argues that Chinese domestic issues are not applicable in Europe. A space to be watched.

China is also in the middle of a major bird flu outbreak. No doubt this, too, will lead to changes in domestic legislation so, UK poultry sector (and possibly others), take note.

Pig trotters

After lunch, we discuss the riveting issue of import conditions for pig trotters. Before anyone accuses me of being flippant, pigmeat exporters reckon that trotters account for 40% of their trade so gaining access to China could see exports shoot up.

|

|

|---|

| Peter Hardwick. |

Our first meeting is with the two Chinese authorities that deal with meat plant approvals and export health certification and import requirements, as well as the conditions for breeding animals and germplasm (look it up).

We manage to get across the important message that our meat production plants have met Chinese production requirements. One more step along the procedural way to China formally “registering” UK plants for imports.

The UK already successfully exports live breeding pigs to China. The next step here is to agree the export of porcine semen. Cue protracted discussion on import conditions, some of which are probably not necessary in our case, but broad consensus on removing or modifying a good number. I would say we are much closer to a workable agreement than previously.

We also discuss bovine semen exports. The Chinese are particularly interested in improving performance in their dairy industry, so there is strong commercial demand but negotiations have stalled over the Schmallenberg virus (SBV) outbreak in Europe.

We don’t expect a commitment then and there – that isn’t the way here – but our invitation to Chinese inspectors to come to the UK to visit our facilities and laboratories will now be considered and may speed up the process of sourcing from UK bulls not carrying SBV antibodies.

Positive relations

I often comes away from these meetings unsure as to what has been achieved because the process is so lengthy. Yet I know it is the same for our counterparts in the EU, the USA and Canada.

A sure sign relations are positive is we are invited to join our Chinese hosts for dinner immediately after the meeting at a local restaurant. This is my first chance to “road test” my progress in Mandarin.

The Chinese dine early, at 6pm or so. Regardless of the region, the principles of yin and yang apply. For example, sugar is often added (in small quantities) to savoury dishes and green vegetables are served with some contrasting slivers of red chilli.

While rice is ubiquitous in China, its role at formal dinners is limited to a filler. The fine dishes – meat, vegetables, fish, seafood – are served first and rice only served at the end if you are still hungry.

Generally, food is served in such a way as to be relatively easy to manage with chopsticks (slippery mushrooms still evade me and tackling a pork rib with chopsticks alone is a real tester).

The other challenge for the innocent newcomer is to recognise what exactly is in front of you. Fish is easy, often brought in live to show it is fresh before being dispatched. But some of the other items are not so obvious. Almost every part of the animal is eaten and the Chinese firmly believe that each part can endow its own qualities. For example, pigs’ feet convey energy and movement.

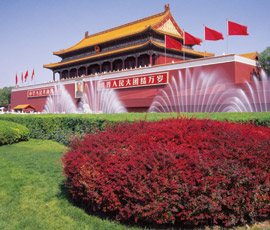

Forbidden City

The Chinese are rightly as proud of their ancient culture as of their varied cuisine. Visiting the old imperial palace complex, known as the Forbidden City, and the Great Wall is an essential part of showing respect. Most meetings will start with a few questions about what you have seen. An enthusiastic response is a good ice-breaker.

No account of Beijing would be complete without a word on the traffic: appalling. Cars are a status symbol and everyone wants to drive. But lane discipline and circumspection appear not to be taught and minor – and not so minor – collisions are commonplace.

I use the excellent Beijing subway most of the time. Upgraded for the 2008 Olympics, the carriages are air-conditioned and a go-anywhere single tariff fare of 2RMB (20p) applies. These get packed at times and a taxi (just 20p/km) can be a better bet if you don’t fancy feeling like a sardine or, to use the much more elegant Chinese analogy, being “squeezed into a picture”.

Dairy market

Growth potential in the Chinese dairy market is colossal. The Chinese drink a quarter to a third of the world average, but even current demand is way beyond domestic production.

The melamine scandal has helped imports, but a quick store check and a visit to an online retailer soon suggest to me there is little UK milk around in China. In fact, the stores I visit have no UK dairy products on the shelves, stocking UHT milk from the USA, New Zealand, Australia and France; butter from France, Ireland, New Zealand and cheeses from Italy, France, USA, New Zealand and Australia.

The biggest presence is German with some imaginative branding. In one case, where a product was branded “La Irlandesa” – which could be translated as “the Irish girl” or “maid”. One to make our Irish friends wince.

I meet the buyer for imported food at China’s main online retailer, 360buy.com, responsible for purchasing 158m RMB’s (£16.8m) worth of products last year. The only country he buys UHT from within the EU is Germany.

The buyer commented quite spontaneously that the company found UK businesses to be unresponsive and slow off the mark, though a visit is planned to the UK later this year to look at import opportunities (including dairy).

There must be opportunities to grow trade from the UK. Clearly other EU countries are already making hay under a sun that is going to shine for some time.

It’s not too late for the UK, but China is all about relationships and those that have developed these relationships first have an advantage.

“I was persuaded to try a ‘jumping frog’ dish but worry ye not – the frogs were not alive; the ‘jumping’ referred more to my reaction after eating it, including desperate calls for water.”

Furnace city

The last leg of my mission to China takes me to Wǔhàn, located in Hubei province in central China. Nicknamed the “furnace city” for its sub-tropical climate, Wǔhàn has a population of just over 10 million and is one of China’s key commercial and transport hubs.

I am here to to present a paper on animal welfare at the grandly named “Global Pig Forum” ahead of the China Animal Husbandry Exhibition. We’re in the right place: China boasts more than half the world’s pigs and pork consumers.

The exhibition was an excellent showcase for the UK’s major pig genetics companies, several of which have joint ventures in China. With Chinese producers achieving little better than 14 pigs sold per sow per year (the UK average is 23), a combination of our genetics and management techniques could see productivity improve by more than 60%.

The conference speakers were very frank and self-critical over incidents in China of dead pigs being found in rivers and the need for the industry to improve its image.

Our large proportion of outdoor sows and the ending of the use of sow stalls, or “crates” as the Chinese call them, was of particular interest.

But all of the papers presented on production and efficiency were based on intensive, sow stall systems. The proliferation of companies at the exhibition selling sow stalls was quite an eye-opener: Danish, Dutch, German suppliers of sow stalls still have plenty of customers in this part of the world.

Nevertheless, my message, that improved welfare can bring wider benefits beyond all the moral issues was well understood. The UK is seen as a world leader on welfare.

Last supper

Time for one last culinary delight before signing off. Being further south, the food in Wǔhàn is spicier, the locals’ anaesthetic use of Sichuan peppercorns is notorious. I was persuaded to try a “jumping frog” dish but worry ye not – the frogs were not alive; the “jumping” referred more to my reaction after eating it, including desperate calls for water.

Visiting a city like Wǔhàn is an essential part of the China experience. Shanghai and even Beijing, to some extent, have made concessions to foreigners with road signs in Pinyin (Latin script), translated menus and shop signs in Chinese and English. Yet outside these major centres you are in deep China, where you get a much stronger impression of the national character.

These cities are at least as intense in terms of hustle and bustle – and execrable traffic. Their people are driven to succeed, they love business and there is an underlying optimism despite the recent economic slowdown. We all have to hope this positive thinking is well founded since our own ambitions to develop exports to this huge potential market will depend on it.

As for how the Mandarin went, I’d score myself a marginal five of 10. More effort needed.

Zaijian (that’s “bye” in Chinese).

See more features on our Rural Living page