Pros and cons of once-bred heifers in beef herd

Looking at an efficient way of increasing cow numbers is always attractive, particularly against the backdrop of a shrinking national beef herd, so could breeding from a heifer once and then finishing her be the answer? Aly Balsom looks at the pros and cons of the system

What does it mean and why would you do it?

The basic principle behind the once-bred heifer (OBH) is to mate a heifer at 15 months, to calve at 24 months. The calf is then weaned, usually within a few days, and the heifer is finished to be sold for slaughter about six weeks after calving.

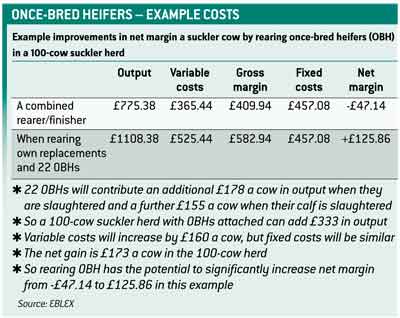

When supply numbers are down, breeding the OBH is an effective way of boosting calf availability and generating more output from the same land area, says Duncan Pullar, head of research and development at EBLEX. “However, it is important to approach this system from an individual farm perspective – the question is whether this system can enhance profit.

“When you can manage the system efficiently, there is no reason why you can’t see a reasonable return,” he says. (see costs)

What are the options?

The OBH system can have various end points, the calf from a OBH can be weaned a couple of days after birth, two-three weeks after calving or six months later. But the key is to set out a plan that best suits your system and stick to it.

However, to get the best from this system, weaning calves as soon as possible after birth and adopting onto a freshly calved cow is ideal, stresses Dr Pullar. “I am not a fan of keeping calves on the heifer until six months. By doing so, it creates doubt over whether the heifer is a slaughter or breeding animal and it means body condition needs to be managed for a greater period.”

An OBH will need to be well recovered and dried off before going to the abattoir, with the earliest slaughter date six weeks post calving.

PROS

Increased productivity

• Produces an extra calf

• Gets a larger carcass from a heifer

OBHs are a huge benefit to the beef farmer – allowing him to do two things at once – rear an extra calf and finish an animal, says SAC’s beef specialist Basil Lowman.

“However, the concept is just as relevant to the dairy herd – by producing an OBH, a dairy producer is increasing the option for his calf.”

For example, cows of lower genetic merit could be bred to Aberdeen angus female sexed semen. Their offspring could be reared to three months and then sold to a beef producer.”

These animals could then be treated as OBH – calved at two, finished, and their offspring could again be managed as OBH.

Selecting stock

Calving heifers once has the added advantage of allowing producers to see how well an animal has calved (see case study). This information can be coupled with individual EBVs to allow more informed selection of replacement animals.

Reduced carbon footprint

Compared to suckler beef, the OBH reduces the carbon cost of the calf because there is not the annual maintenance cost of a cow, says Dr Pullar.

“For an OBH the cost of growth is against her beef value and therefore the calf is nearly free – there is just energy costs of calf production.”

The concept of the OBH is relevant to the whole industry. It will produce more beef, more efficiently, while reducing carbon foot print, says SAC’s beef specialist Basil Lowman.

CONS

Management

The practicalities of managing the OBH has been one of the main reasons why the system has not taken off in the UK, says Dr Pullar. “Because the heifer will be finished soon after first calving, body condition must be monitored all the way through.”

Don’t underestimate the control and monitoring that is needed to get animals to the correct bulling weight, keep the condition on, calve and then finish, he says. “When you take your eye off the ball, they’ll be less chance of making a profit.”

Ideally, heifers should be weighed every six weeks and OBH animals identified when they are weaned. Heifer growth rates can then be tracked to ensure they are on target to be two-thirds of their mature weight at breeding to be ready to calve at two years.

Carcass worth

In the current system, the OBH’s worth is greatly under-rated. Because an OBH is classified as “unclean” she will fall into this lower pricing category, says Dr Lowman.

However, a recent Asda scheme has been set up to guarantee the value of once bred heifers

A study carried out by AFBI Hillsborough found breeding a heifer once reduced killing out percent (from 59% to 54%) and increased fatness of the carcass in terms of fat classification and body cavity fat compared to an unbred heifer slaughtered at 24 months.

However, taste tests carried out by Asda found meat from OBHs had the same eating quality as clean beef.

Animal welfare and perception

There is a slight queasiness in slaughtering an animal soon after it has given birth, says Mr Pullar. But, when stock is looked after properly, there shouldn’t be any animal health and welfare issues, says vet Keith Cutler. “There is no reason why this system cannot work. But it is crucial heifers are grown enough to rear and deliver a calf,” he says.

“As with any animal, the welfare of the freshly-calved cow must be considered.”

COSTS

|

|---|

Farmer case study – Asda’s Proven Heifer Scheme

To help suckler producers improve efficiency, Asda has developed a proven heifer scheme to ensure beef farmers receive a fair price for once-bred heifers, explains Asda agricultural development manager Pearce Hughes.

“The programme ensures OBHs receive the same pence a kilo as clean cattle. The scheme is not encouraging an OBH system in its purest sense, instead we are removing the risk of putting heifers in calf.”

The scheme takes heifers up to 36 months, but requires heifers to rear calves for a minimum of 12 weeks.

“We want to encourage suckler farmers to put as many heifers to the bull as possible. By doing so, they are provided with a genetic fast track, allowing them to identify the best mothers and select out problem cows.”

And this strategy has proved valuable for Worcestershire suckler producer Adam Quinny, of Reins Farm, Redditch. “Putting most heifers to the bull provides us with another point of measurement when they calve so we can make a decision on which animals to use as replacements,” he says.

Before joining the scheme, and choosing to expand and introduce Saler genetics, a lot of heifers were run empty because of poor market value. Now Mr Quinny is confident to put heifers to bull because of a guaranteed price from Asda.

All heifers weighing 380-400kg at 15 months are put to the bull and performance accessed when they calve in the spring at 24 months.

“Good-performing animals are kept as replacements and poor animals managed as OBHs,” he says.

Calves from OBH are then weaned at six-seven months with OBHs dried off and put on the finishing ration four-five weeks after weaning. They are then finished and sent to slaughter in January-February.

“We may have delayed marketing a heifer by three months by going down this route, but we have produced an extra calf, received added income and been able to evaluate genetic performance.”

However, managing the heifer throughout, particularly through pregnancy, is essential, he says. “Putting a heifer to a good, easy-calving terminal sire with a short gestation is crucial. When you don’t, and she gets knocked around at calving, you won’t see the growth rates.”

OPINION – Aly Balsom

With increasing pressure to reduce carbon emissions and produce a sustainable national beef supply, a system that gets more value from an individual animal seems an attractive option.

But with animal welfare at the forefront of consumers’ minds, even if farmers accepted the OBH system more widely, public perception could be an issue.

However even when producers are unwilling to go down the OBH route in its purest sense, putting more heifers in calf is an excellent way of assessing performance at first calving, selecting the best replacements and speeding up genetic improvements.

Price reward at slaughter will ultimately be a key driver, and maybe not until the national grading system reflects the carcass worth of the OBH will the system take off. But programmes such as Asda’s heifer scheme could help raise awareness of the concept and encourage more producers down that route.

The OBH system won’t suit everyone and, in a sense, it shouldn’t – managing heifers in such a way needs top-notch management and when done half heartedly, the system would be far from cost effective.

• Tell us what you think of the once-bred heifer system on our forums at www.fwi.co.uk/forums