Danish genes help beef herd become fully polled

Next year, Lopemede Simmentals will reach a milestone, becoming one of the first and largest fully polled Simmental herds in the country.

For owners John Rixon and his son Eddie, it is the fruit of eight years of hard labour, sourcing polled genetics from Denmark and slowly progressing their 200-head herd to pure polled.

See also: Beef Focus Farm: Secrets to achieving top 1% performance

John was first attracted to Europe because of the greater number of quality, polled homozygous bulls available in comparison with the limited UK supply.

Lopemede Simmentals facts

- Runs 200 pedigree breeding females

- Herd was established in 1997 and will soon become fully polled

- Spring calving

- 300ha – 140ha is rented

- Buys 300 ewe lambs in the autumn. They are sold as theaves at Thame Sheep Fair in July

In Denmark, a vet is legally required to dehorn calves and because of the high cost of the procedure, it has encouraged a large proportion of Danish farmers to select the polled gene.

“Initially I could see the advantage of having polled cattle, and Denmark was accessible.

“I felt it was an unnecessary stress on the animal and people. The beauty is we now don’t have to dehorn,” says John.

He believes the shape of the head also contributes to easier calving. But the benefits don’t stop there.

Eddie says another advantage of buying bulls from Denmark is that they can take advantage of the country’s high health status.

“This is especially important to us as we run a closed herd.”

Breeding

John has bred the herd pure over time by selecting for homozygous polled genes – whereby both genes are recessive – and up-breeding females.

“Some of the cows will be polled going back seven generations,” adds John.

See also: UK v Denmark: How pig producers compare

Maternal traits remain a priority when selecting bulls. Sires must have good calving-ease figures and be positive for milkiness. Two bulls have recently been purchased by the Rixons from the Vingegaard herd – Vingegaard Kabull P and Vingegaard Kantor HP – to introduce new bloodlines to the herd while maintaining hybrid vigour.

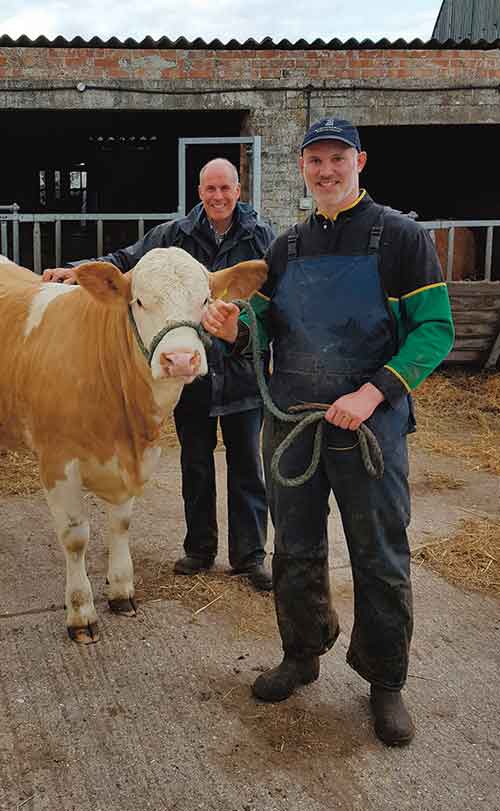

John (left) and Eddie Rixon

“Both bulls have recognised and proven male and female genetics through previous generations, such as Raceview King, Vingegaard Mon Cheri and Gretna House Supersonic.”

Heifers are bulled at 14 months to calve at two years. They are synchronised and get AI’d twice before being put in with a sweeper bull.

Last year, the Rixons used the Canadian sire PHS Polled Worldwide 14W on some heifers. He was chosen for his low birth weight.

Meanwhile, the cows are all served naturally at a ratio of 30 cows to one bull.

The whole herd calves indoors in the spring, which Eddie says is fundamental to their low-cost system because it enables them to make the best use of summer grazing once cows and calves are turned out.

He adds: “The cows aren’t provided with any supplementary feed because they milk well off grass.”

In July, calves are introduced to creep feed ahead of weaning in October, when males and females are separated and moved to the other holding for fattening over the autumn and winter.

The best 30 heifers are kept as replacements each year and 70 are sold for breeding at 12 months old.

Adding value

Part of the reason the Rixons switched to polled genetics is because of the value it has added to their business.

“Because there are not that many herds in the UK specialising in polled homozygous genetics, it allows us to add a premium to what we do,” explains Eddie.

Typically, homozygous breeding bulls sell for £5,000, whereas heterozygous bulls sell for £3,000 and heifers average £1,500, with stronger, homozygous heifers achieving £3,000.

Aside from a small proportion of females, the majority of stock is sold direct off farm.

“We don’t want to risk taking stock to sales and then not sell them and have to bring them back home.”

Bull beef ration

- Wheatfeed

- Maize germ

- Biscuit meal

- Soya

- Rape

- Palm kernel

- Wheat distillers

- Soya hulls

- Urea

Selling stock direct from the second farm also enables the family to limit the risk of introducing diseases to the main breeding herd at the home farm.

Because the herd has been able to source from a wider pool of polled genetics, the Rixons haven’t had to compromise on other traits such as growth rates.

They have shortened the fattening period by two weeks through selecting bulls with high 200-day and 400-day weights. As a result, daily liveweight gains are hitting 1.7-2kg on average, enabling all bulls to be finished at 12-14 months.

The last 15 bulls averaged 405kg deadweight and graded U+ 3+.

All feed is milled and mixed on farm, with bulls fed ad-lib (see “Bull beef ration”) and heifers fed 2.5kg daily.

“What I like about milling [our own feed] is the feed is kept fresh,” says John. He believes milling only what is needed avoids spoilage.

“We are able to deliver a constant product at 12 months. It works because we only winter the animal once,” he adds.

The fact the Rixons finish a proportion of their own bulls gives them a commercial focus too.

“It needs to stack up for us and the people who buy our progeny,” says Eddie, who encourages buyers to give them feedback on how their progeny performed so they can note performance of certain bloodlines.

“We get feedback on grade and we can relate that back to the breeding,” says John.

“You don’t want big, rangy cattle. You want animals that will add meat and flesh at a young age, but not be overweight either. The one thing with the Simmental is they add meat easily,” says John, who used to own a butchery business.

See also: Scan beef cattle eye muscle to cut feed costs

Future

Recording intramuscular fat and eye muscle scores also helps to ramp up finishing performance.

Currently, only a proportion of the bulls are scanned once they reach between 600-700kg liveweight, but the Rixons believe even bigger gains can be made in the future by scanning everything. And the EID investment they have just made should help facilitate this.

“It is part of the animal you can’t see, so the only way you can measure it is to scan. It gives you the assurance that you are selecting the right EBVs,” adds Eddie. He says more and more of the commercial customers are now asking for this information.

“The demand for data is becoming more apparent. The more data you have, the more robust it is – and it gives you added confidence in the progeny you are buying.”

In the future, Eddie, who studied agriculture at Reading and worked at Kellogs in marketing and at Waitrose as a food buyer before returning home to farm, would like to undertake a Nuffield scholarship to explore how value can be added to beef.

“I think the big thing is not enough is being done to positively promote beef.”