How a South West dairy became the UK’s best bred herd

© Ann Hardy

© Ann Hardy Ian and Max Davies say they have never bred a cow for the show ring, yet they have a string of championships to their credit from top UK events. We uncover what’s behind their success.

The father and son team retain a depth of knowledge about each animal’s pedigree, individually breed every cow and heifer, and take a pride in nurturing and promoting their family lines.

This is what keeps them motivated and prevents milking from being a drudge on their 120ha (296-acre) half owned, half rented farm.

See also: Meet the 2020 Gold Cup dairy farmer finalists

Farm facts: Davlea herd

- Milking 140 Holsteins

- Yielding 10,000 litres of milk a cow a year at 4.12% fat and 3.29% protein

- Pedigree livestock sales make up about one third of turnover

In return, the herd they have developed at Higher Farm near Ilminster in Somerset has richly rewarded them in both the show and sale rings.

Accolades range from UK Dairy Day supreme championship (2018) to the Royal Welsh interbreed championship (also 2018) and, most recently, the prestigious Premier Herd Competition, awarded at UK Dairy Day last month.

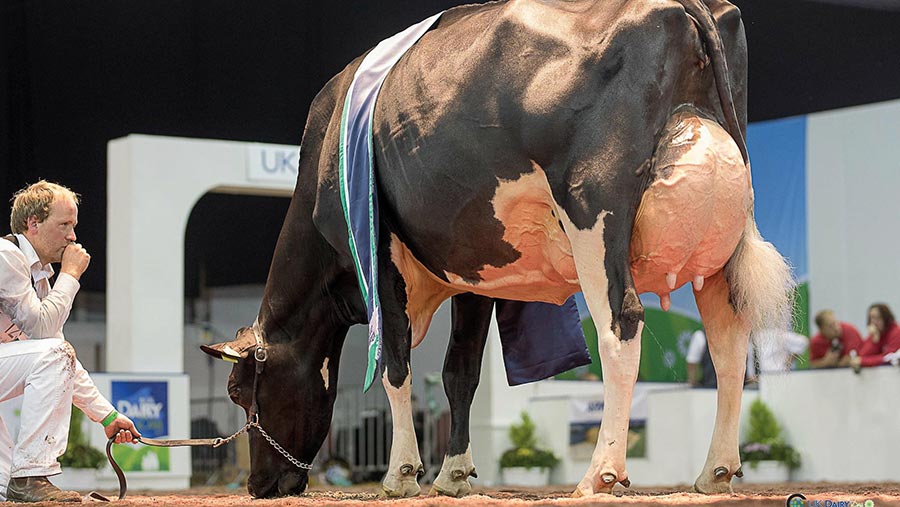

Champion Davlea Bradnick Alicia © UK Dairy Day

Last year, their reduction sale – which saw their Davlea herd go from 160 to 115 milkers – grossed more than £200,000 for the family business, with a top price of 6,500gns.

Even in an average year, livestock sales from the herd would make up about a third of the business turnover, while exhibiting cattle at shows feeds the team’s interest and fuels demand for its stock.

How these cattle came to reach such heights is a story of family commitment through three generations, starting with Ian’s father, Bryn, who established the herd in Sussex in the 1970s.

In 2004 it moved to Illminster in Somerset under the management of Ian and Max.

Production

In the West Country it has gone from strength to strength, with production topping 10,000 litres at 4.12% fat and 3.29% protein (305 days, twice a day milking), while sompatic cell counts (SCC) run from 100,000 to 150,000 cells/ml depending on the time of year.

Despite working with old buildings, most dating to the 1960s, part of this performance is attributed to the installation of new cubicles last November. The new cubicles are 2.7x1m and bedded with sand over lime.

“They were inadequate before, but we had no idea, as there were more than enough for the cows,” says Max Davies. “But too many cows were standing and on the day we made the change, we saw an increase in production of 3.5 litres a cow overnight – entirely due to longer lying times.”

He says the herd had no new cases of mastitis for four months after the installation, but cases did edge upwards after turnout.

The Davlea herd © Ann Hardy

Breeding

Breeding the cattle which have served them so well has involved close attention to detail, in particular to linear type profiles, which Mr Davies insists must show wide chests and good udders as a priority.

“A wide and balanced cow is the kind everyone wants,” he says. “We never bred for a show cow, but have got them by breeding width and balance.”

Controversially, he takes little note of the overall, composite Type Merit index, but prefers to drill down to individual traits.

“I prefer to look at linears,” he says. “Type Merit can be misleading because it can lead to cows with minus chest width and stature which don’t have the ability to process forage very well.”

For modern farming, he looks for functional traits, including feet and leg composite, SCC and daughter fertility index (FI), although he admits he will fall into negative territory for FI if everything else in the bull is right.

“We’ve always bred for functionality, but now there are more facts and figures and enough bulls out there to choose from,” he says.

In terms of production, fat and protein are now the priority since the farm moved to a cheese contract with Wyke Farms.

“More and more attention must be paid to milk solids, especially in selling stock to Ireland where they like to see fat and protein in the cow families,” he says, suggesting the team were “lucky” to have used some high component bulls, even on the previous liquid contract.

Type classification is considered essential to both breeding and livestock sales and is described by Mr Davies as “a good unbiased opinion”.

Max Davies © Ann Hardy

It has served the farm well, as the herd today boasts 60 cows classified Excellent and 80 Very Good, in a milking portion which is now back up in number to 140 head.

The bulls which have delivered this success include Val-Bisson Doorman, Walnutlawn Solomon, Picston Shottle and Braedale Goldwyn.

New names added in recent years include Farnear Delta-Lambda, Stantons Chief, Vogue Solarpower, Walnutlawn Sidekick, Stantons Applicable and Tappenvale Medalist, some of which are sons of bulls the Davies had previously chosen not to use.

Mogul is a case in point, according to Max. “His daughters were the shorter and rounder type we weren’t seeking, but I can see the benefit of his health traits and high-quality udders in his sons and grandsons, like Comestar Lineman, Seagull-Bay Silver, and Mr Welcome Mogul Lental,” he says.

The desire for uniformity across the herd sees no more than five or six bulls used each year. As Mr Davies puts it: “We don’t want Liquorice Allsorts – we prefer to have a stamp.”

Future demand

To avoid having too many stock bulls in any cow’s pedigree, a final straw of high fertility British Blue is used on anything which hasn’t held to sexed or conventional dairy before the Holstein sweeper goes in.

Developing cow families is at the heart of what the Davies do, and it is their names that have built the Davlea herd’s reputation.

These include Alicia, Ashlyn, Lulu, Nugget, Pledge and Raven, the latter tracing to a cow from Markwell in the US, whose best daughter, Davlea Shottle Raven EX94, is still going strong at 130t and has a daughter classified EX95.

It is families such as these which have spread the Davlea magic across the UK for more than four decades and are likely to sustain it into the future.

“We think we’ll still be viable with this number of cows if we can keep the value of pedigree up,” says Max. “People will always want to milk nice cows, and we are fortunate that cows we have bred are the kind they seem to want.”

Max Davies’ advice on getting into pedigree

- Pedigree is not as fashionable as it once was, but investing in sound genetics can pay

- Even a commercial cow from the market could be a starting point from which to grade up

- Don’t focus on numbers, nor be afraid of using tried-and-tested, proven sires

- It is worthwhile working with the best herds if possible, having personally spent time on the acclaimed Fermes Jacobs in Quebec and Indianhead Holsteins in Wisconsin