How one dairy is managing forage stocks for weather extremes

© MAG/Shirley Macmillan

© MAG/Shirley Macmillan Three weather apps and a bespoke spreadsheet are helping to feed cows cost-effectively at Clive Hall Farm – despite more extreme weather patterns affecting forage stocks for this spring block-calving herd.

A legacy of some “lean management” training about 15 years ago, the spreadsheet is used by contract farmer, tenant and landowner Phil Asbury to plot cow numbers (dry and milking) and feed demand (dry cow roughage or milking-quality forage, and concentrates).

See also: How a beef farm is managing grassland to face extreme weather

Farm facts

Clive Hall, Winsford, Cheshire

- 213 cows

- Friesian genetics with some crossbreds

- Calving in 12 weeks from early February

- Average yield 5,100kg at 4.9% fat and about 3.5% protein

- Feeding 750-800kg blend a cow

- 63ha grazing platform

- 35ha support block for silage, which is clamped (fourth cut baled)

- Cows wintered in cubicles and outside

- Youngstock reared off farm from weaning until calving

The farm, near Winsford in Cheshire, is contract farmed by Grasslands Farming.

It has focused on a block-calving system based around making best use of grazed grass, with a 14% protein blend flat-rate fed in the parlour.

But Phil is now seeing that techniques for difficult weather periods – such as on/off grazing, or grazing surplus grass rather than clamping it – have become part of the regular routine.

“In total, we need 420t dry matter [DM] of silage and hay a year for the herd to keep it in a stable feed position.

“This is about 350t DM clamp silage plus 40t DM of haylage/baled silage and 30t DM hay.

“We know we need to feed 70-80t DM over summer,” says Phil.

“This is all for cows: heifers go to the youngstock unit after weaning and 35 come back in-calf every January.

“Cull cows go in November or December, so our stock numbers average about 200 cows year-round,” he explains.

Feed budgeting

Having previously worked with consultant Kay Carson to improve farm efficiency, Phil has continued to use Kay’s spreadsheet to track numbers, budget and monitor KPIs (he also has Kingswood software for grazing management and Herdwatch for cow health and fertility).

Phil Asbury using the budgeting spreadsheet © MAG/Shirley Macmillan

It means that he knows what he needs to buy, when, and how much of it, throughout the financial year starting 1 May.

This is becoming increasingly important with changing weather patterns for the farm.

In October, for instance, he had recorded an average 205 cows milking on a diet of 5kg DM silage, 2kg of blend, plus grazed grass.

For November, the budget was for 188 milking cows fully housed on a diet of 15kg DM silage and 3kg of blend.

Populating the spreadsheet through winter until year-end, it calculates that he needs 211t of DM to get to the end of March 2026, for both dry cows and next season’s freshly calved milkers.

“What we have in stock now means we are going to be OK until mid-March.

“If we run out, we have to buy 50t DM silage if there isn’t enough grass after turnout,” he says.

Impact of weather extremes

Phil has noticed that the farm is not as drought tolerant as it used to be.

“We have heavy soils and can grow 16-18t DM/ha in a very good year, and average around 14-15t DM/ha, of which we use 12t DM/ha.

“The farm is growing the same amount, just at different times of year.

“But we are not harvesting a surplus these days – we graze it due to prolonged wet and dry spells,” he says.

Managing these wet and dry spells is becoming more of a challenge without suppressing grass growth – Phil says that poaching is damaging the plant root structure.

And while growth rates still peak at 100kg DM/ha a day and continue to grow at 65kg DM/ha a day in summer before tailing off, these days he finds this happens as soon as there is a seven- to 10-day period without rain.

It has taken all this year for grassland to recover from wet autumns in 2023 and 2024.

“We didn’t finish our grazing round in 2023 and there was lots of damage – more when we turned out in spring 2024.

“The result was we made no silage off the grazing platform last year, for the first time ever,” he says.

Grazing was difficult throughout 2024 because, although cows went out in February, they were housed again two weeks later.

After 10 days inside, they went back out when March offered drier conditions, but more rain followed until the end of May.

© MAG/Shirley Macmillan

“So they were out, and in again. We ran out of silage and bought some, but cows had a poor peak yield.

“It was a poor year: we fed 1.1t of concentrates a cow and only yielded 4,800 litres,” he reflects.

Although this year started with a “kind” spring, May became really dry.

Phil says they grew only what the cows could eat; from June, through July and August, the farm dried up. Reviewing trends, he says that 2018 was also a very dry year with no silage reserves.

“It cost us a lot, and we needed to learn from that.

“For more forage security, we rented extra ground – our support block – and made sure we managed a deficit.

“As a result, we no longer bale surplus grass, only to feed it back as silage two weeks later.”

Tools for grazing management

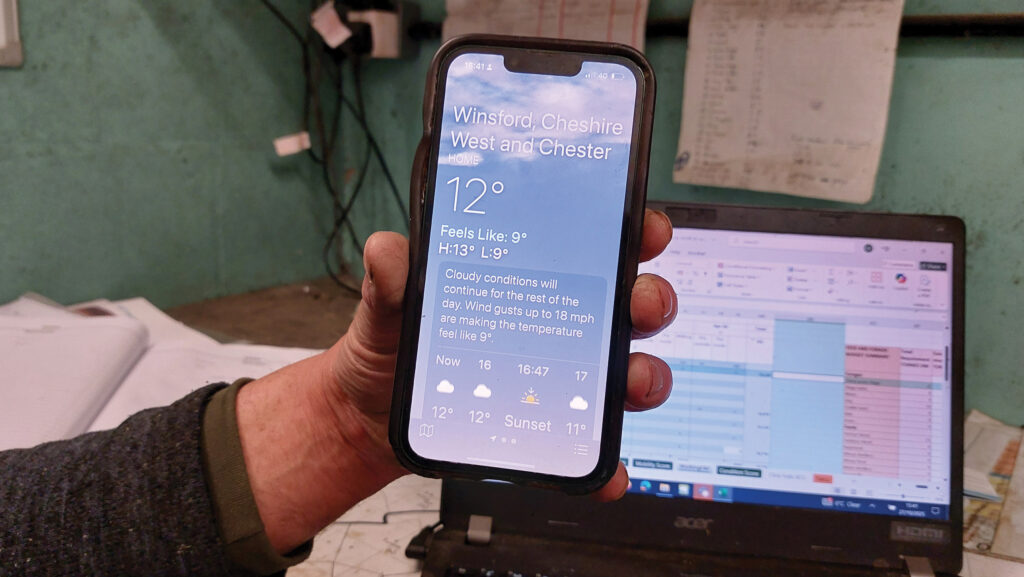

To better pre-empt a feed deficit when dry weather is on the cards, Phil started using local weather apps on his phone to look at forecasts 10 days and two months ahead.

Using loacl weather apps © MAG/Shirley Macmillan

By weekly plate metering (sometimes twice a week if growth is rapid) and using the grazing software, he can predict if growth rates will plateau, or fall.

He can then decide whether to graze grass earmarked for silage, rather than incurring harvesting and feeding-out costs, or substitute 2kg DM grass a head with 2-3kg of concentrates “and keep monitoring”.

Making more silage to be secure of quantity and quality at an affordable price has been important for farm resilience.

Phil is not keen on buying huge stocks at a high market price, or of “questionable quality”.

The farm also makes some of its own hay to control quality.

Herbal leys to mitigate drought

To keep cows grazing through drought, the whole farm has been direct-drilled with herbal leys, albeit with variable degrees of success in establishment.

Maintaining them in an “aggressive” grazing system is also hard work, however, Phil is pleased to see more chicory and clover appearing this year.

“We are also looking at reducing stocking rate – which is quite heavy at 3.4 cows a hectare – and slowing the round to help,” he says.

He adds that clover in swards has been more successful, reducing artificial nitrogen inputs by about 30kg N/ha to 170kg N/ha.

Using real-farm data to make feed decisions is giving the farm flexibility to adapt its forage production and utilisation.

Phil’s view is that it replaces decision-making based on guesswork.

The skill, he adds, is in getting useful information from all the data logged in the spreadsheet – plans, budgets and cost structure.