How partial diet offers cost-effective solution to cow health

Mastering dairy cow diets can seem like a fine art. Get it right and your herd will benefit from high milk yields and good health; get it wrong and there will be a plethora of issues to deal with. But it is possible to balance nutrition and costs.

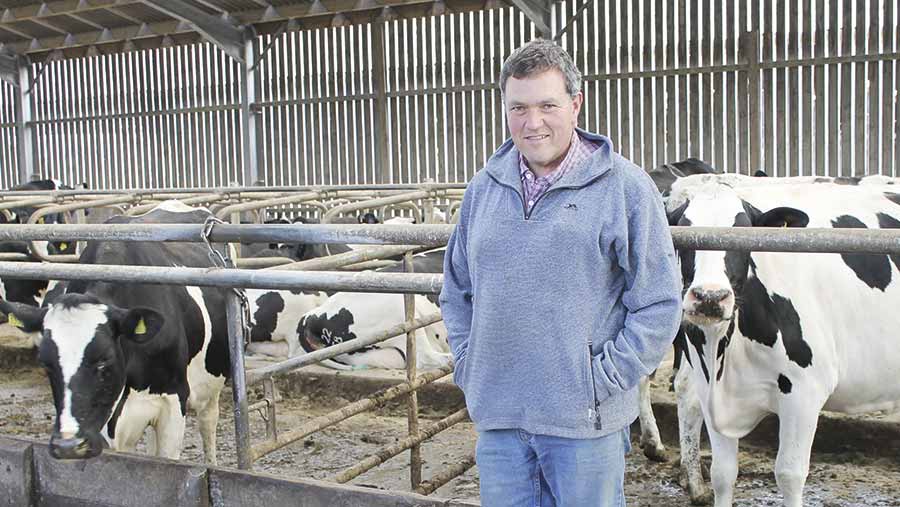

Cornish farmer Mark Button is managing to strike the right balance with a partial DCAB diet, maximising productivity while also curbing costs.

Mr Button switched to a partial DCAB diet with a calcium binder in 2014, and has seen excellent results with his 940 Holstein cows.

“We calve all year round and have a dedicated shed for our dry cows,” explains Mr Button, who farms 567ha at Polshea Farm, St Tudy.

See also: Data shows routine testing of forages is key to preventing milk fever

Cows are dried off every Friday and split into two groups – far off and close up. Cows spend four to five weeks in the far-off pen before moving into the transition group and are then moved to a loose yard about one week prior to caving.

Ration differences

Far-off dry cows receive a mix of 6kg of brewer’s grains, 4.5kg of ground straw and 20kg of grass silage. “To keep management simple, the close-up group receive 80% of the same mix, with the addition of 4kg of maize silage, an extra 4kg of brewer’s grains and calcium binder X-Zelit,” adds Mr Button.

The biggest change with the new diet is the inclusion of brewer’s grains in the ration, explains Pete Davis, ruminant nutritionist at CMC.

“Effectively, the old diet was a partial DCAB diet, but using magnesium chloride to create that partial DCAB,” he says. “Now it is created with brewer’s grains instead.”

The benefit of using brewer’s grains is the increased palatability, compared with magnesium chloride.

“Brewer’s grains give the same level of DCAB that we previously attained from magnesium chloride, but also suppress butterfat in early-lactation animals, meaning they keep a bit more energy for themselves and milk production rather than putting it towards making butterfat – making it easier to keep the energy status correct,” Mr Davis adds.

Grass silage is included in the diet to mimic the ingredients animals will later receive in the milking cow diet, but it does create an issue with high potassium and calcium levels, warns Mr Davis.

“To counteract this, we add the brewer’s grains, maize silage and a calcium binder, which binds the additional calcium that is in the diet. We calculate the quantity carefully so it binds the exact amount of calcium that we need to remove from the diet – leaving enough in the remaining ration to meet the dry cow’s requirements.”

The subsequent DCAB that is created takes the edge off the potassium loading from the grass silage – creating a simple diet that is consistent and requiring little effort from a management perspective, he adds.

Improvements in cow health

So, what is the benefit at ground level? Prior to switching the diet, the farm struggled with health issues and consistency, says Mr Button.

“We had a few issues with milk fever and retained cleansings, and while our milk fever percentage was low across the herd, at about 3% to 4% – we have now managed to reduce this to less than 0.5%.”

Mark Button

The diet has also benefited pregnancy rates, with cows getting back into calf much easier – increasing all service pregnancy rates from 22% four years ago to about 25% now, adds Mr Button.

“We have also seen better-quality colostrum as a result of more protein being driven into the cows, which of course makes for better calves coming through.”

Mr Button has worked closely with his vet, who has noticed dramatic improvements to herd health over the past three years. “Clinical milk fevers are a thing of the past and other factors are under much better control,” explains Phil Elkins, director at Westpoint Veterinary Services.

“Retained membranes are rarely seen and usually associated with twins or dystocia. While metritis hasn’t been eliminated, it is far more responsive to treatment when it does occur,” he adds. “Maintenance of rumen fill and body condition is also more consistent – giving the cows the best start for their upcoming lactation.”

Ration costs compared

The simple management and the ability to be flexible with feed sources – as well as incorporating protein into the ration through the silage and brewer’s grain – gives Mr Button a cheaper system, compared with a full DCAB diet.

Cost savings are a modest £8-12 over the 49-day dry period. However, the partial DCAB diet is significantly cheaper than a full DCAB diet or a full X-Zelit diet, which would add another £8-12 to the total costs, says Mr Davis.

Pete Davis

“The ethos of the farm is to maximise the feed value of what they grow,” explains Mr Davis. “While there is a cost for the calcium binder, it does guarantee consistency. Grass silage quality varies depending on the cut but this helps balance out any variations, giving farmers security and more flexibility for any movements in the diet.”

For the most efficient herd, it’s crucial to look at the dry cow diet as just one part of the bigger picture, says Mr Button. “The dry cow period sets the tone for everything but it’s important to look at the herd as a whole and create a diet to make the business as profitable as possible.”

Rations compared over a 49-day dry period |

|

|

Old partial DCAB |

£65.39 |

|

New X-Zelit partial DCAB dry cow diet |

£64.26 |

DCAB feeding: What’s the difference between full and partial diets?

The dietary cation-anion balance (DCAB) feeding system is frequently used to prevent milk fever by creating acidic conditions in the blood, which promotes calcium mobilisation from the cow’s bones and prevents blood calcium levels from dipping.

The demand for calcium at the start of lactation is so high it cannot be provided solely from the diet, so it’s important to prepare the cow’s body for this calcium mobilisation, which is done by keeping calcium levels low during the transition period.

The DCAB approach offsets inputs of positively charged cationic salts, such as potash and sodium – which make the blood less acidic – with acidifying negatively charged anions such as chloride and sulphate.

Full DCAB diets use mineral supplements to create the acidic conditions. While this works well with good management, it is expensive and (if not fed accurately) too high a calcium input can increase the risk of milk fever, explains Pete Davis, ruminant nutritionist at CMC.

“Partial DCAB diets are a simpler and lower-cost option for farmers. They involve careful utilisation of feeds to minimise sodium and potash intake, usually with the addition of magnesium chloride to create the optimum DCAB level of between +50mEq/kg DM and -50mEq/kg DM [a milliequivalent (mEq) is a measure of the chemical combining power of the electrolyte in a fluid] – the lower the value, the less chance of milk fever.”