Chop or bale? Our cost/benefit analysis explores the answers

Deciding whether to incorporate or bale and sell straw is always something of a moving target, with input price volatility, supply-and-demand issues and improving nutrient research all playing their part in the outcome.

Each year the break-even price is surprisingly low, even when you take into account input price fluctuations on one hand and varying diesel prices on the other. It’s fair to say that the market price of straw bears little resemblance to the market value of oil, potash or phosphate. In 2008, when potash was 97p/kg, phosphate was £1.49/kg, red diesel was expected to reach 75p/litre, the break-even price for straw was £29.82/t, but the ex-farm price ranged from £30-£48/t.

Organisations such as the Potash Development Association have extensively researched the amount of additional nutrient content removed when the straw is baled. As such, when the tonnage of straw removed is known, the nutrients required to replace the deficit can be calculated in detail and are significantly less than the textbook figures used four years ago.

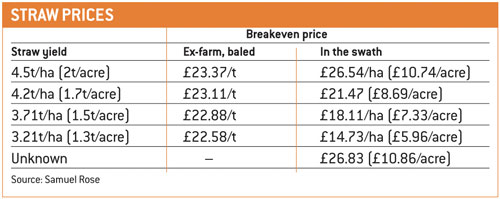

At the time of writing, potash is 60p/kg, phosphate 95p/kg and red diesel 65p/litre. In the tables below. the break-even cost of selling the straw is shown for various yield scenarios and a baled-and-stacked contract charge of £10/bale is assumed.

There are several factors other than inputs to consider. Min-till rape establishment systems suit straw removal to ensure maximum soil to seed contact, optimum establishment and minimum disease risk, so chopping the straw would require another pass to bury it.

With inversion tillage systems, any trash is buried, so chopping or baling does not affect cultivation practices. There is a hassle factor when straw is sold – extra compaction from balers, reduced organic matter in the soil, implications for timeliness and so on – but this can be hard to quantify and has been left out. Some published research investigates the link between organic matter and the water-holding capacity of the soil, and its effects on yield, and no doubt as further research is undertaken, robust guidance will be available.

Nutrient cost

The table shows that the nutrient cost of the straw differs significantly in line with the yield of straw. Standard figures (from the RB209 Fertiliser Manual) for straw removal where yields aren’t known, assume a fresh weight straw yield of 50% of crop – so a 9.9t/ha (4t/acre) wheat crop will yield about 5t/ha (2t/acre) of straw.

These are high straw yields for arable areas with modern combines and growth regulator programs to minimise straw length, where you’d expect straw yields in the region of 2.5-3.7t/ha (1-1.5t/acre). But RB209 has to be high to cover all growing scenarios on all farms. It is clear from both a buyer’s and a seller’s point of view that knowing the weight being bought and the yield of the crop is key to agreeing a sale value or certainly the cost of production.

With all the above in mind, the key market driver this harvest will be supply and demand. Combines are already rolling in the east and while there is a knock to grain yields, the dry spring has also resulted in tiller abortion and very short straw length, even where a robust growth regulator programme hasn’t been used.

Therefore, there is very likely to be a shortage of straw to send west. Recent trade locally has seen prices of £99-111/ha (£40-45/acre) in the swath, considerably above the break-even of £26.8/ha (£10.86/acre).

Livestock producers should act early to make the most of long-term relationships and secure deals with existing suppliers. For the arable farmers, why not consider leaving the chopper switched off this year?

There will be demand for your straw, but with the rising price of fertiliser, don’t overlook the benefits of an old fashioned muck-for-straw agreement.As always, whether you chop or bale, it should be a considered business decision, and not just from force of habit.

Guy Banham is a rural business consultant at Samuel Rose.