How a lucerne living mulch is working on Danish arable farm

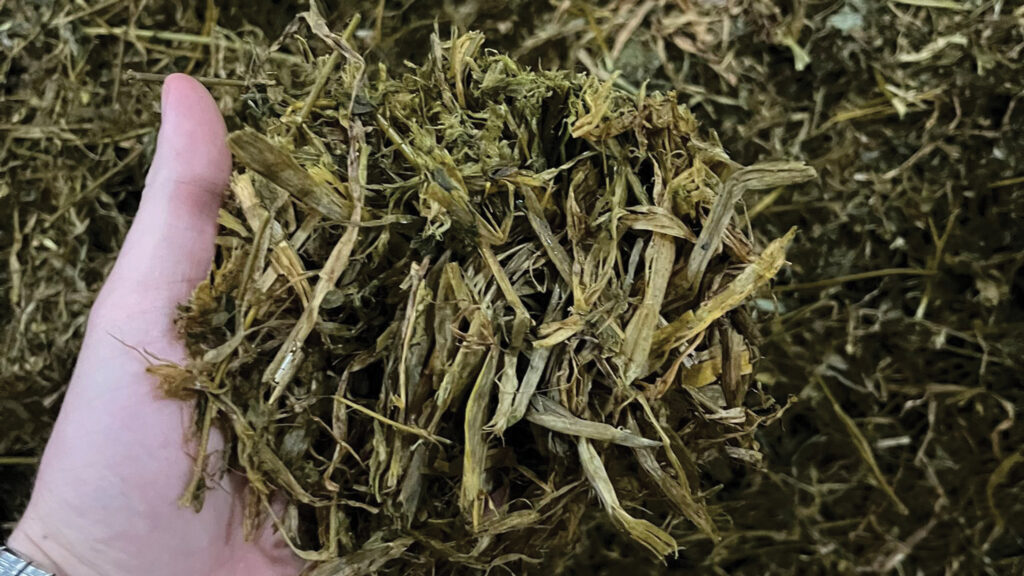

Cutting stubble increases lucerne regrowth © Frederik Larsen

Cutting stubble increases lucerne regrowth © Frederik Larsen A living mulch based on the perennial crop lucerne is allowing Danish farmer and agronomist Frederik Larsen to harvest more sunlight and produce two crops each year, while reducing costs and improving environmental outcomes.

By having lucerne as an understorey in a rotation dominated by winter cereals, he has been able to grow and harvest cash crops with a minimal yield penalty, while also getting at least one forage crop in the autumn.

See also: Regen field vegetable growing: Can it be done?

Also known as intercropping, the system he has trialled since 2018 on the family farm at Barlosegaard combines no-till crop establishment with perennial crops – with lucerne helping to capture nutrients and fix nitrogen, as well as suppress weeds.

The greatest risk is yield loss in the cash crop, he acknowledges, but adds that where species with the right root systems are chosen, a 5-10% penalty is the most that should be accepted.

Frederik Larsen’s reasons for using a living mulch

Frederik Larsen © Louise Impey

- Keeps fields green and capturing sunlight

- More carbon sequestered – so more income

- More reliable than cover cropping

- Easier and less time consuming – no need to drill summer cover crops

- Creates competition with weeds

- Suited to winter cereals rotations

- Captures nutrients from depth and fixes nitrogen

- Better water infiltration

- Reduces erosion and protects soil

- Extra income from forage and crop residues.

Soil erosion

Frederik originally implemented his living mulch system to prevent soil erosion, but has since found it to be more reliable than the use of cover crops and also helps to improve water retention, as well as sequestering carbon.

“It’s a form of future-proofing too,” he says.

“Rotations based on winter cereals are less affected by climate change. Added to that, lucerne has the ability to fix up to 300kg/ha of nitrogen when it’s produced in the traditional way.”

The 250ha farm’s latitude in Denmark is similar to that of the north of England, he points out, so it could work well in the UK with the right management and understanding of the ecological principles involved.

“It’s about plant growth,” explains Frederik. “With green cover and living roots in place, the plants are capturing sunlight and feeding the soil with root exudates.”

© Tim Scrivener

Ecological principles

There are three ecological principles to apply to intercropping, he says.

“These are competition, complementarity and compensation. When you understand these, the species will work together in a synergistic way and the system will be stable.”

Competition can be intraspecific or interspecific, he continues. “If it’s intraspecific, the two species work against each other and compete for resources, but where you have interspecific competition, they are more likely to be in harmony.”

In the same way, complementarity means the two species help each other and make resources available, adds Frederik.

“Think about nitrogen fixing and nitrogen uptake as an example. You get better use of resources when the two species complement each other.

“It matters more with roots, so having species with appropriate root systems is important.”

Compensation applies to compensatory growth – something that happens when one species comes under stress, perhaps from drought or herbicide use, allowing the other species to benefit.

“It helps to derisk the system and removes variability. In this system, we see compensatory growth happening after the lucerne is mown.”

Frederik stresses that species complementarity is really important, as yield loss can occur where they compete.

He suggests using a legume with winter dormancy, such as lucerne or clovers, in a cereals rotation, to promote growth.

“Ideally you want a legume which is dormant in the winter and can survive cold temperatures, but has good late spring growth. The cereal cash crop has to be able to grow away first.”

Controlling the living mulch while not killing it is a delicate balance and can be risky, he accepts. “You have to manage it so that it reshoots after the cash crop harvest.”

Living mulch tips

- High risk of yield penalty in cash crop

- Make use of root complementarity

- Ensure good tillering in cereal crop

- Amend agronomy accordingly

- Autumn forage cuts possible

- Is there a lucerne forage market?

- Suitable for mixed farming systems.

Year 1

In the first year, starting with a cash crop that can be undersown with lucerne is key.

Frederik recommends oilseed rape, but with the proviso that it is put in a reasonably clean field. He cross-drills the lucerne on an angle in a second pass.

© Frederik Larsen

“You can’t use post-emergence broad-leaved herbicides or you will kill the living mulch,” he says. “But you can get a pre-emergence mix on, and there are graminicides that can be used.”

As it nears harvest, the oilseed rape canopy opens up and lets light through, encouraging the lucerne. “So you do need to get the oilseed rape off in good time, or the lucerne will drag it down.”

There’s been no yield penalty from the lucerne in the first year, he confirms. “We’ve had OSR yields of 3.8t/ha and 4.2t/ha in such a situation.”

Mowing the field right down to 10cm after harvest is essential so the lucerne reshoots from the crown. This rapid regrowth comes from its taproot, which acts as an energy source.

The field is then mown again a few weeks later, with the forage used to feed neighbouring dairy cows.

Some 8t/ha of silage, or 3t/ha of dry matter, have been produced, with 90kg of N/ha removed.

© Frederik Larsen

Year 2

Year 2 sees a winter cereal being established, which is when the living roots effect starts to be apparent.

Again, clean fields help, so low herbicide rates are used shortly after the lucerne forage harvest.

The seed rate of the winter wheat cash crop is increased to boost tillering, and a good autumn herbicide programme is recommended.

A generous dose of early nitrogen gets the wheat going in the spring and ensures that it tillers.

To prevent the vigorous lucerne getting too tall, Frederik exploits its sensitivity to acetolactate synthase (ALS) inhibitor herbicides in an operation he describes as “chemical mowing”.

This takes place at roughly the T0-T1 timing, with low herbicide rates.

“It’s really important to have a weed-free period for 14 days before and after the wheat is flowering,” he reports.

“If you don’t control the lucerne, you won’t have a wheat crop.”

He has achieved a 9t/ha wheat crop in this way. “The wheat’s nitrogen uptake is earlier than the lucerne can supply it, so we applied 200kg/ha of nitrogen.”

The harvest sample was remarkably clean, he notes, but the lucerne did contribute an extra 1% moisture. “A stripper header would be ideal or we could swath a field.”

After harvest in year 2, his attention turns to getting more from the lucerne. Again the field is mown, to get the lucerne to reshoot, with chopped straw a potential barrier to this happening.

Really good regrowth is seen after 2-3 weeks, when he goes back into the field to mow and bale it. Some 85 large bales were made, representing 2t of dry matter a hectare and removing 65kg of N/ha.

© Frederik Larsen

Year 3

In year 3, he has planted winter oats – but stresses it could be any winter or spring cereal.

Having used herbicides after the lucerne harvest and before the crop was drilled, the field was relatively clean.

“Make the most of any pre-emergence grassweed herbicides as there’s not much you can apply in the spring. And again, get in with an early spring nitrogen application to get the oats growing.”

His chemical mowing technique is used again in the spring, although oats can be very competitive, and he puts them in the same rows as the previous wheat to prevent damage to living roots.

A yield of 9.5t/ha came from the oats, he reports.

© Frederik Larsen

Learnings

Removing the cereal straw at harvest helps to increase lucerne yields and provides another income stream, says Frederik.

Slugs can be an issue – in one field in 2024, the lucerne was grazed so heavily by slugs he was unable to get a forage crop.

A seed mix of white clover, red clover and lucerne was used to plug the gaps.

Assigning an economic value to the benefits isn’t straightforward, he accepts, as there are additional management costs with the system.

“The main cost is the lucerne seed at €150/ha (£129),” he says. “The mowing is costed at €25/ha (£21). Of course, the alternative is a cover crop, which would cost me €125/ha (£107).”

In terms of extra income, the value of the nitrogen fixed is €155/ha (£133) and the forage is €805/ha (£690), both calculated after two years.

He recognises it is possible to capture more value from the system if there are livestock on the farm.

It’s realistic to expect up to four seasons from the lucerne, he adds, and urges farmers to consider an earlier cash crop harvest by up to 14 days.

“That gives more time for living mulch regrowth and means that you could get two autumn cuts.”

Other possibilities include wholecrop harvesting and earlier establishment of the cash crop so there’s time for grazing or silaging in the autumn.

© Frederik Larsen

Frederik Larson of Agroganic was sharing his experience with BASE-UK members at the organisation’s recent annual conference.