Proactive approach vital in protecting blackgrass herbicides

© Tim Scrivener

© Tim Scrivener Herbicide-tolerant weeds can prove costly with some UK wheat growers spending up to £130/ha on herbicides and still failing to manage their blackgrass infestation.

However, experiences around the world show those who have not seen herbicide resistance yet can hold out and avoid these extra costs, by following some simple steps.

Harry Strek, scientific director of Bayer’s Weed Competence Centre points to some farms in the US that are free from glyphosate-resistant weeds.

See also: Analysis: Why glyphosate reapproval has stalled

Although rare, some farmers have not adopted the glyphosate-only system, instead sticking with older practices involving pre- and post-emergence herbicides and occasional tillage.

“It shows it is possible to hold out, while surrounding farms are seeing glyphosate-resistance problems.”

Harry Strek

There is no reason why this can’t be the case for other weeds in other countries and there is much to gain in taking a proactive approach to resistance.

Resistance levels have to approach quite high levels before farmers accept they have a resistance problem, he says.

“This is the point when it starts to affect agronomy and yields.”

Getting to this point is fairly rapid.

Using a hypothetical model assuming there is one weed in a field which produces 10 offspring a season that are randomly distributed, levels reach 10% in five years.

This is the point when farmers start to see it.

“However, at this stage it is usually too late to keep it from taking over the field as data shows that once you see resistance in your field, it stays.

“It can take decades to get levels back down after you stop using that active, depending on the weed and farming system.”

Being proactive pays

That is because you are constantly selecting for resistance by taking out competitor weeds.

Dr Strek highlights an example where 15-30% of the weed population of a field showed ACCase resistance despite not seeing an ACCase-inhibitor herbicide for nearly 20 years.

One common misconception is resistance only spreads from neighbours. However, data shows it can also evolve independently in each field and this is good news, as farmers can reduce this risk.

Bayer’s UK herbicide product manager Phillippa Overson says that’s why “the incentive is far greater for weeds.”

With fungicides, it just takes one farmer to inadvertently allow resistance develop and this will spread to neighbours.

For herbicides, farmers have far greater control of populations on their own farm and will directly see the benefits of resistance management.

But this longer-term approach can be less of a priority on contract-farmed land.

Dr Strek highlights Argentina, where nearly 70% of cropped land is rented and the poor economics have seen a move to single-year leases.

“This is perhaps why resistant weeds emerged more rapidly than in some other areas of the world,” he says.

What is herbicide resistance?

In order to manage resistance development, growers need to understand what resistance is and how it develops.

A resistant weed is defined as one that survives and reproduces after receiving a normally lethal dose of the herbicide.

“You get survivors due to naturally occurring mutations that appear initially at extremely low levels.

“They are already there and heavy use of the same mode of action without any other weed control measures means you are selecting for resistance year after year after year,” Dr Strek explains.

How reduce pressure?

Minimising resistance pressure means reducing overall weed populations through the increased use of cultural and mechanical techniques and integrating them with herbicides. The key steps are:

- Know your weed spectrum and understand your weed

- Develop a plan such as drill the worst field last to enable more stale seed-beds and include crop rotations

- Diversify weed management

- Enhance crop competitiveness

- Aggressively manage weeds (full rates and robust mixtures)

- Maximise herbicide activity with good application technique and proper timing

Those who have not yet seen blackgrass, can follow this to avoid getting in the costly situation seen further east, says Dr Strek.

“Some are still seeing 70-80% efficacy with Atlantis (iodosulfuron + mesosulfuron) this is worth protecting.”

But it’s not just about preventing blackgrass problems, resistance management also has a role in protecting other valuable chemistry such as flufenacet, where resistance has not yet been found. “Now may be the time to act.”

Ms Overson had already sensed a shift at last year’s Cereals.

“It was the first time that I have been approached by a farmer saying ‘I have chemistry that is still working, so what should I do to protect it?’.”

Resistance testing

Latest development areas in resistance testing

More rapid resistance testing and a new prediction model aimed at farmers are two key areas of development at Bayer’s Weed Competence Centre on the edge of Frankfurt.

While the ultimate goal of an in-field test is still some years off, the agrochem firm has already seen advances in testing in their laboratories, speeding up the process.

“Knowing what type of resistance you have is important, as it determines what herbicide can be used,” says Roland Beffa, who leads the weed-resistance research team.

Target site resistance is where the herbicide no longer fits the target site of the enzyme and this kind of resistance is specific to the mode of action. In contrast, metabolic resistance is where the weed breaks down the active and this kind of resistance is not specific to the mode of action.

Changing to another mode of action can control the resistant population if it has target site resistance, but if it has metabolic resistance, it may not help.

“You may see loss of efficacy in some classes, although other compounds in the class may still work.

“It depends on the molecular structure,” he says.

One thing to look out for is that weeds can accumulate resistances, as in multiple resistant populations, and so can have resistance to more than one mode of action, warns Dr Strek.

Testing methods

Resistance testing

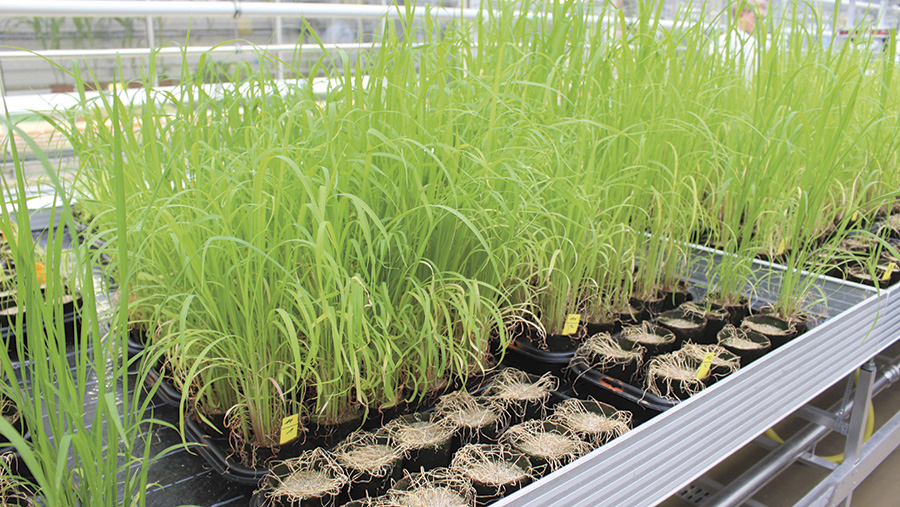

The standard method for testing seed is to grow the plants and then carry out glasshouse bioassays.

But this is a lengthy process that takes three months,” says Dr Beffa.

This means seed testing is largely carried out between seasons, to enable farmers to tweak their approach in the following season.

However, a new assay has been developed using live plants that can give results within two-to-three weeks.

“It involves selecting eight plants randomly in a field, cutting off their roots and posting the shoots in a special pack to the labs in Frankfurt.”

For enhanced metabolism, shoots are treated in a herbicide mixture and are tested to see if the tissue metabolises the active ingredient.

In the future, he believes molecular markers will streamline the process, as it would just involve analysing DNA, which is relatively stable and can be analysed in dried plant material.

For target site resistance, DNA sequencing is already used.

This testing is used to investigate reports of herbicides not working, as the cost is still too high for routine on-farm testing although this could come down in years to come.

However, Dr Beffa adds some of these cases are later found not to be the result of resistance, suggesting an application or other agronomic problem.

Another key area of research is the development of a resistance prediction tool, based on actual farm data.

Bayer is jointly involved in a project with the University of Braunschweig in Germany investigating a series of fields across three sites south of Stuttgart.

The investigation was sparked by a complaint in 2008 and looked at how resistance spread, says Dr Beffa.

It collated data from each farmer including cropping, cultivations and drilling dates.

They discovered several key factors which led to the development of ALS-resistant blackgrass, which are ranked in descending order of importance:

- Frequency of winter cereals in the rotation

- Frequency of spring crops in the rotation

- The number of different crops in the rotation

- The proportion of ploughing in the rotation

- Proportion of delayed drilling

- The number of modes of action of herbicides

- The number of applications of herbicides

- The number of ALS-inhibitor herbicides used

Using these indices, his team has developed a model and they are validating it on German farms.

“The plan is to then validate it in France in the next 12 months and within one-to-two years growers in Europe will have access.”

It will be useful in showing different management scenarios, for example what will the population be in five years when adopting a particular approach to weed management and how much would it cost to put it right.

He believes this may go some way in helping persuade farmers to be more proactive in preventing resistance developing on their farm.

Weed Resistance Research Centre

Globally, there are nearly 250 species of weeds with herbicide resistance and each country faces a particular challenge.

For example, US farmers are fighting glyphosate-resistant palmer amaranth and waterhemp and in Australia, ryegrass is their blackgrass.

And the number of resistant species is increasing across the world for all modes of action.

Harry Strek highlights that the world relies on just a few modes of action. “More than three-quarters (77%) of the global herbicide market involves just six mode-of-action classes.”

On top of this, no new modes of action have been discovered in the past 30 years and none are expected in the near future.

But Dr Strek says there is a dire need for new resistance-breaking herbicides.

The widespread adoption of GM Roundup technology in some parts of the world has had a negative impact on research.

“It has led to many institutes and universities scaling back their weed research programmes,” he says.

To help address this, Bayer established the Weed Competence Centre in 2014, in Frankfurt with 14 full-time staff and is investing a greater proportion of its budget into weed research.

“We did weed research before, but we needed to bring it together in one place. We are collaborating with other organisations including Rothamsted Research in the UK and the Australian Grains Research and Development Corporation, as it is too big a task for a single company to solve.”

The centre has three objectives:

- Be the leader in weed research, understand resistance in weeds, how research mechanisms work, how it arrives and can be managed

- Take this knowledge to develop new practical solutions, both chemistry and non-chemistry

- Communicate the messages to farmers and key stakeholders

Dr Strek highlights the key role of communication.

“We need to find ways of successfully getting the messages across, while not glossing over the extra effort that is needed to adopt an integrated approach.”

Richard Hinchliffe

Case study: Richard Hinchliffe, Thorne in South Yorkshire

Flufenacet is a critical pre-emergence active in the fight against blackgrass and like glyphosate, growers should look to minimise resistance risk.

That is according to a grower and Nuffield Scholar Richard Hinchliffe who manages the family farm of 560ha near Thorne in South Yorkshire.

He believes without it, the weed would be much more difficult to control.

To date extensive monitoring by Bayer has not found any flufenacet resistance and there remains a theoretical risk.

Liberator (flufenacet + diflufenican) is the basis of weed control for many farmers, but needs careful stewardship to safeguard it for years to come.

Opting for a proven mix where diflufenican protects flufenacet is a solid first step.

But this needs to be backed up with other actives at pre and post-emergence and a wide range of cultural controls.

A pre-emergence programme built around flufenacet is at the heart of Mr Hinchliffe’s weed strategy, which also includes hand rouging.

His deep interest in herbicide resistance is due to growing seed crops, where he takes a zero tolerance to weed control.

But weed control is still a challenge.

“Although the vast majority of our acreage is hand rouged for grassweeds, we do have pockets of blackgrass that chemistry can no longer give acceptable control.”

Consequently, Mr Hinchliffe plans to stop using Atlantis (iodosulfuron + mesosulfuron) next year.

Also there is ACCase resistance and clethodim has also proved ineffective.

Mr Hinchliffe sees cultural techniques as having a role alongside chemistry and is considering bringing more spring cropping into the rotation.

Cropping on the family farm includes winter wheat, oilseed rape, winter and spring beans on better land and spring wheat.

He hopes to find other solutions as part of his Nuffield Scholarship, where he is investigating how other farmers are dealing with herbicide-resistant weeds around the world.

“Not only do I hope to get ideas and innovations to use back on our farm, I also want to help the wider farming industry.”

He is visiting farmers and researcher dealing with resistant weeds in the USA, Australia and South America.

Visiting Bayer’s Weed Resistance Competency Centre was part of his scholarship.