Dining wild-style

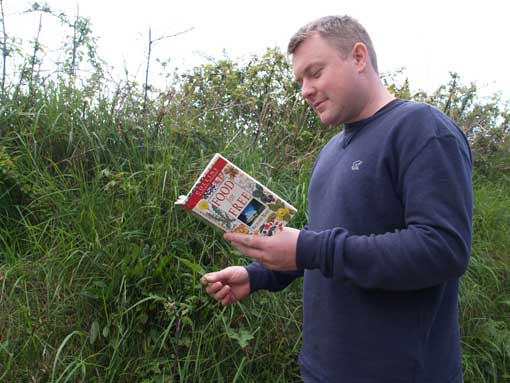

Chef Owen Hall scrutinises a leaf he has plucked from the hedgebank, matching it to an image in a plant reference book.

It is a pennywort, an edible plant, so Owen pops it into his mouth to test its suitability for inclusion in one of the most unusual meals he has been asked to prepare.

He is scouring the hedgerows with his junior sous chef, Leon Fitzgerald, and Julia Horton-Powdrill, a founder of a Pembrokeshire dining club that champions foraged food.

Although Owen is keeping the menu for this Really Wild Dining Club meal under wraps, he does let slip that one of the more unusual dishes he will serve is terrine of grey squirrel.

Diners won’t be told the ingredients of each of the eight courses until after they have eaten which, in the case of the squirrel pate, is probably a wise move.

Before Owen and his team at the Wolfscastle Hotel near Haverfordwest can get busy in the kitchen, there is the matter of gathering the ingredients from the countryside. Fortunately they won’t need shotguns for the squirrel dish because a local game enthusiast has already delivered that part of the menu, so they are concentrating on the greenery.

They have an expert guide in Julia because she can identify most plants growing in the wild. Her father was a country doctor who had a background in botany and zoology before studying medicine and he encouraged Julia to forage in the hedgerows for edible plants.

“He taught me to identify plants and how they could be used medicinally,” she says. “He was a great naturalist. When we went for a walk we would always come back with something to eat, such as mushrooms or berries, and it rubbed off on me.”

One of Julia’s most memorable finds was a giant puffball that appeared on her lawn. “It was delicious sliced and fried,” she recalls.

Her passion for wild food culminated in the Really Wild Food and Countryside Festival at St David’s, which she launched with her husband, Brian Powdrill. This event takes place each autumn – this year on 4-5 September – and visitors are encouraged to reconnect with the rural environment through food walks, talks and activities. Local chefs also put on cookery demonstrations using wild food.

More recently, Julia and Brian have created the Really Wild Dining Club. Like the festival, it is non-profit making, with any surplus funds donated to local good causes. Julia says forming the dining club was the natural next step after the festival.

The main criteria for both the festival and the dining club is that the food being offered for sale or on the menu must originate from the wild or contain ingredients from the wild. The aim is to encourage people to experiment.

“We want people to look at what food they have around them and to appreciate what’s there,” says Julia. “The idea is to get chefs thinking outside the box by foraging in the countryside.”

Julia has found an ally in chef Owen Hall because he already knows a thing or two about wild food. He often forages along the estuary near his home for sea spinach and marsh samphire.

He can identify sorrel and some of the more common edible hedgerow plants, but is grateful of Julia’s knowledge on this particular foraging expedition and the guidance from two books she is armed with, Food for Free and The Forager’s Handbook.

Today, they gather sorrel, mustard garlic, gorse flowers, primroses, violets and pennywort by the basketful. Owen admits he would use more wild food in his restaurant dishes if gathering it wasn’t such a time-consuming business, but that doesn’t diminish the value he sees in nature’s bounty. “It just wouldn’t be practical to me to use this type of food from day to day, but we all as individuals should understand more about what is available in the countryside,” he says.

There are professional wild-food harvesters who collect to supply restaurants, food producers and shops. “Chefs can be paying around £25 per pound weight for wood sorrel and £20 for morel mushrooms,” says Julia. She is adamant, however, that people should respect the countryside. “We certainly don’t encourage the wholesale massacre of hedgerows,” she insists. “Wild food should be a supplement rather than something you live off.”

Gloves are needed for gathering young nettles which will form the main ingredient of a haggis that Owen will prepare. He won’t be working from recipes for tonight’s feast, preferring to make it up as he goes along.

As Owen, Leon and team get busy in the kitchen preparing the food, the diners start to arrive. One woman confesses to being a “wild food virgin” as this is her first time, but there are also more experienced diners, including retired tinplate worker Ron Williams and his wife, Wendy, who have been to all but one of the dinners since the club’s inception. They live in Llanelli, but rather than making the 90-minute journey tonight they are camping overnight nearby.

For them, the joy of these meals is eating foods they wouldn’t otherwise dream of trying. “I used to be really fussy about what I ate, if I didn’t like the way it looked I wouldn’t touch it. Now I find myself eating things like sea anemones and razorfish,” says Wendy.

First up on this evening’s menu is a trio of breads incorporating sea spinach, asters and purslane gathered from Llangwm Estuary. Next is conger eel, fresh off the boat at Milford Docks.

Then it’s the grey squirrel terrine, served with pennywort. Owen has had some fun with this dish by combining it with hazelnuts. When the restaurant’s owner, Andrew Stirling, unveils its origins there is surprise all round. The diners count themselves lucky that they have tasted such an unusual meat.

“I wouldn’t order it if I saw it on a restaurant menu, but I did enjoy it. It just shows what can be done,” says Toby Vincent, who has come along tonight with his family.

Andrew Stirling shares the enthusiasm of his chef for wild food and enjoys the reaction of the diners when he tells them what they are eating. “Owen says he didn’t know there was so much in the car park that we could eat!” he laughs.

Julia hopes that, encouraged by the success of the Really Wild Dining Club, similar clubs will establish in other parts of the UK.

She admits that it wasn’t too long ago when people who collected wild foods were considered “hippyish crackpots”, but that there is now a great deal of interest in foraging, survival and using fresh and local ingredients.

“Those of us who get out there and actually forage are beginning to appear normal,” she says.

The interest in wild food foraging seems to go hand-in-hand with the passion for allotments, homegrown vegetables and fruit.

What is available depends on the season, but according to Julia’s guidebooks there are at least half a dozen plants available most months.

And with food being lined up as a possible target for VAT, one of the Really Wild Dining Club members points out that wild food is at least one source of nutrition that won’t get a tax slapped on it.

Julia’s recipe for Spring Pesto

Chop 500g of wild garlic leaves and process in a blender with 200ml of olive oil and 75g of walnuts. Add some grated, locally-produced hard cheese if desired.

Free food in the countryside

• Wild garlic grows in woodland and is identifiable by its garlic-like smell and long lush leaves. Unlike domestic garlic, wild garlic is championed for its leaves rather than its bulb. It has a very similar taste to domestic garlic, yet slightly milder. The leaves can be eaten raw or cooked and work well in salads and soups.• Marsh Samphire also known as Glasswort is often referred to as “poor man’s asparagus”, the juicy stems are abundant on salt marshes.

• Primroses can be used to perk up jams and also candied to decorate pastries.

• Elder is a fast-growing shrub with sweet-smelling flowers that can be used to make cordial or can be deep-fried in batter. The berries can be combined with blackberries to make delicious filling for pies.

• Sea Spinach this plant is common on banks and shingle by the sea and can be used in the same way as garden spinach.

• Sorrel grows in grassland throughout Britain and has a lemony taste. It works well in soup or in a sauce to accompany fish.

• Nettles are best picked young and can be used in soups and risottos.

• Sweet Violets Common in hedgerows, these delicate blue flowers can be used in salads but are most popular when made into crystalised sweets.