Meat eaters or vegetarians: Who has the better arguments?

© Alex Milan Tracy/SIPA-USA/PA-Images

© Alex Milan Tracy/SIPA-USA/PA-Images Almost exactly a year ago, renowned environmentalist George Monbiot addressed a debate at the Oxford Farming Conference on the motion “This house believes that, by 2100, meat eating will be a thing of the past”.

At the start of the debate, chairwoman Julie Robinson asked for a show of hands among the audience of almost 400 whether they believed the days of meat consumption would indeed be consigned to history by the end of the century. About 20 raised their hands.

See also: Interview with George Monbiot at Oxford

The debate then ensued, with Mr Monbiot, supported by Compassion in World Farming’s chief executive Phil Lymbery, setting out the arguments as to why they believe meat production has a limited shelf life.

In particular they focused on the environmental impact of livestock farming, notably the claimed inefficiencies of converting plant protein to animal protein with all the costs in terms of resource use and greenhouse gas emission.

The farming side of the debate was put by North Wales hill farmer Gareth Wyn Jones and Norfolk dairy farmer Emily Norton, focusing on the landscape benefits, the cultural heritage and the nutritional aspects of livestock production.

Mr Jones recalled how generations of hill farmers had preserved the land and how nature and farming can live as one. He conceded consumers might need to eat less meat for it to be sustainable in the long run, but he believed consumers would not turn their backs on it altogether.

At the end of the hour-long debate, the audience, whose make-up contained many farmers and landowners, cast their votes. A further 100 had been persuaded to support the motion, that meat eating would indeed be a thing of the past by 2100.

This result clearly demonstrates the persuasiveness of the non-meat eating argument, and that in itself presents a real threat to the long-term prospects of meat production in a world challenged by a fast-expanding population, resource depletion and climate change.

So what are the counter arguments and how can livestock producers defend their practices, their traditions and, potentially, their very existence?

Nutritional aspects of meat

© Monkey Business/REX/Shutterstock

What the vegan/vegetarian lobby says

A quick look at the Vegan Society website reveals a host of arguments vegans put forward to explain why they believes meat eating is at best unnecessary, at worst detrimental to human health.

All the nutrients humans need can be found in non-meat and non-dairy format, they argue. For example, fruit and veg provide essential vitamins, protein is readily available from beans, lentils, chickpeas and soya, while calcium can be obtained from calcium-fortified plant drinks and tofu.

Eating nuts and seeds daily can provide essential omega-3 fat, while vitamins D and B12, iodine and selenium can all be obtained from daily supplements.

According to the Vegan Society, obtaining nutrients this way rather than through meat (and dairy) bestows health benefits. “Some research has linked vegan diets with lower blood pressure and cholesterol, and lower rates of heart disease, type 2 diabetes and some types of cancer,” it says.

On the flip side, the anti-meat lobby points to the fact meat, milk and eggs all contain higher levels of saturated fats and cholesterol. This, they say, promotes heart disease, obesity and even impotence.

Indeed, research by Oxford University, which has been studying the link between diet and health in a cohort of about 60,000 people in the UK over 20 years has found a 30% reduction in heart disease among vegetarians.

“A vegetarian diet provides a statistically significant lower risk of heart disease compared with meat eating, which we think is primarily due to lower levels of circulating cholesterol,” says Tim Key who leads the research as part of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition.

The anti-meat lobby also points out that most incidents of food poisoning are caused by contaminated animal flesh.

What the meat sector says

See also: Farmers reject demands for a 14% tax on red meat

The counter-arguments are many, especially in relation to the nutritional benefits of meat and dairy.

According to the AHDB, red meat is high in nutrient density, and a major source of protein.

The type of iron found in red meat (haem iron) is more easily absorbed and used by the body than the iron in plant foods, and it is also a good source of readily absorbable zinc, which is important for the healthy functioning of the immune system, growth, wound healing and fertility.

Red meat is also a significant source of B vitamins and has recently been found to make an important contribution to vitamin D intakes. It also provides other minerals such as potassium and selenium, the latter being an important antioxidant.

Stories about the high fat content of red meat are also exaggerated, says AHDB. On average, fully trimmed raw lean beef contains just 5% fat and fully trimmed raw lean lamb 8%. About half of the fat found in red meat is unsaturated, which is believed to be healthier.

It also contains small amounts of omega-3 fats, which help to keep the heart healthy, while red meat is naturally low in salt.

Meanwhile, Robert Pickard, professor of neurobiology at the University of Cardiff, warns many plant-based alternatives are actually packed with artificial ingredients, having gone through extensive chemical processes in order to mimic the taste and texture of the real thing.

AHDB also points out that anaemia is the biggest single nutritional deficiency in the UK, with 2-5% of men and women suffering from the condition. Eating red meat is one way of overcoming it.

It is also worth noting high numbers of food poisoning incidents come from eating vegetables and salads.

Nutritional aspects of milk and dairy products

© Dairy UK/www.milk.co.uk

What the vegan/vegetarian lobby says

It’s not just meat which gets a bad press health-wise. It is often pointed out humans are the only species to drink the milk of another species, and the only ones to drink it into adulthood.

Yet about two thirds of the world’s population are “lactose intolerant” – unable to cope with cows’ milk, as most people stop producing the enzyme lactase between the age of three and five.

That does not in itself mean “milk is bad”. But it is often claimed the high levels of saturated fat in milk and dairy products can increase the risk of heart disease, which is why many public bodies around the world – including Public Health England – recommend that people restrict their intake.

High calcium diets have also been linked to a higher incidence of prostate cancer, while dairy is believed to aggravate irritable bowel syndrome and Crohn’s disease.

What the dairy sector says

Dairy UK is quick to dismiss the “myths” surrounding consumption of the industry’s products.

Despite its saturated fat content, there is no significant association between milk and dairy foods and heart disease or type 2 diabetes, it says. Some evidence suggests dairy may actually be protective in terms of cardio disease.

Indeed, it claims milk may even help break the obesity cycle. Speaking at a dairy and health seminar in London last year, Kevin Whelan from King’s College London said consuming dairy as part of a calorie-restricted diet could aid body fat loss.

“The protein in dairy may help in making us feel full and delay our desire to eat,” Prof Whelan said. “Calcium may also reduce the amount of fat that is absorbed in the gut.”

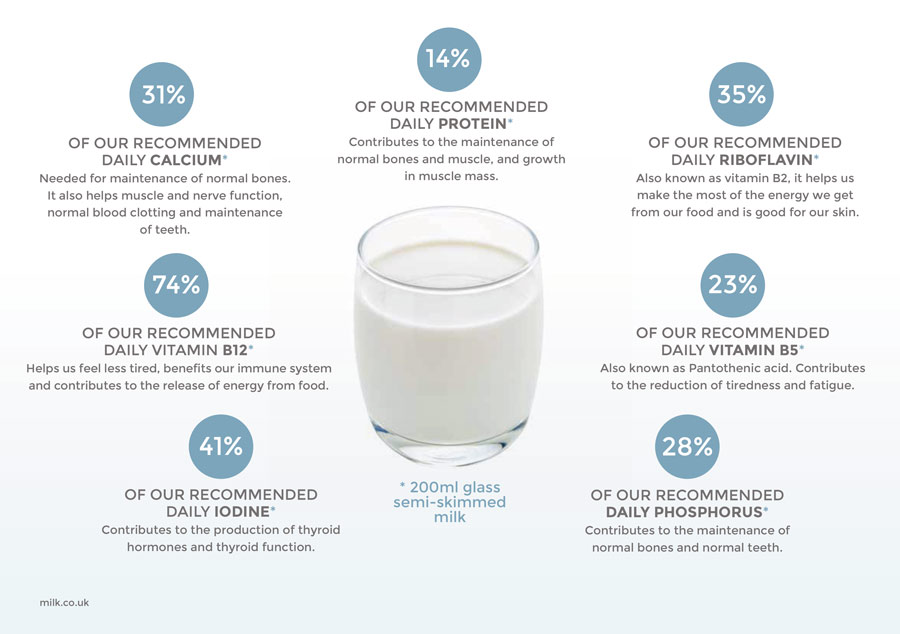

Dairy products are also highly nutritious. A single cup of milk provides much of the calcium, vitamins, iodine and protein the body needs each day.

Dairy UK also points out, while lactose intolerance may be an issue in some parts of the world, in established “dairy” countries, only 5% of the population have this condition.

Cancer risk from meat

What the vegan/vegetarian lobby says

Perhaps the trump card in the anti-meat lobby’s pack is the claimed link between red meat and cancer.

This was spelled out in October 2015, when the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) concluded “processed meats are carcinogenic” and “red meat is probably carcinogenic”.

The findings were based on the analysis of about 800 separate pieces of research in relation to meat consumption and colorectal cancer. It prompted media claims such as “bacon and sausages are as bad as plutonium” and “processed meats rank along smoking as cancer cause”.

A recent report from Marco Springmann of the Oxford Martin Programme on the Future of Food, suggests imposing a tax of 14% on UK red meat sales and a 79% tax on processed meat would help reduce consumption, saving 6,000 UK lives every year and contributing more than £700m to the national economy by reducing healthcare costs

Some health advisers also point to the way red meat is cooked. Blasting it at high temperatures can lead to the formation of harmful compounds, such as heterocyclic amines, which can cause cancer, they say.

What the meat sector says

Scientific opinion linking meat to cancer is questionable and is often selectively quoted.

For example, one recent study printed in the journal Cell Metabolism suggested people with high animal protein in their diets had similar cancer risk to people smoking 20/day.

While that grabbed the headlines, what was frequently overlooked was that, in the older age bracket (65+), the link between high animal protein content and increased cancer risk was reversed.

As for the claims by IARC that processed meat is “definitely carcinogenic” and red meat “probably carcinogenic”, it is worth remembering those classifications only refer to the potential “hazard” and make no attempt to assess the actual “risk” in real world situations.

For example, the IARC’s assessment is based on the consumption of 50g/day of processed meat, which might raise bowel cancer incidence by 18%. But, in the UK, the average consumption of processed meat is just 17g/day.

Put another way, about six in every 100 people will get bowel cancer in their lives. If they eat three rashers of bacon every day, that will rise to seven people in 100.

As for red meat consumption, Tim Key from the Cancer Epidemiology Unit at Oxford University says his studies show “no significant difference” in the incidence of colorectal cancer compared with non-meat eaters.

However, this is based on average consumption rates of 70g/day of red meat – the maximum amount recommended by the NHS. If this is pushed higher, then there is some evidence of a limited increase in cancer risk.

According to the NHS, it is wise to cut down on meat if you eat more than 90g/day, but it is fine to include it as part of a balanced diet. It also suggests selecting leaner cuts, limiting processed meats and cooking in a way that lets the fat run off.

Environmental impacts

© Florian Kopp/imageBROKER/REX/Shutterstock

What the vegan/vegetarian lobby says

Given the inherent inefficiencies of converting plant protein to animal protein, the area of land needed to feed the same number of people through livestock farming increases massively, putting huge pressure on climate, habitats and ecosystems.

Greenhouse gas emissions are a particular problem. In the UK, it is estimated that 10% of the country’s 496m tonnes carbon dioxide-equivalent greenhouse gas emissions are generated by agriculture, in particular methane (5.6%) and nitrous oxide (3.3%) coming from livestock production.

The recent UK Committee on Climate Change recently called for a reduction in meat and dairy consumption as a way of reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The 3-7 million ha of grassland released from livestock production by a 20-50% reduction in beef and lamb numbers could be used to grow trees and biofuels, which would be better for the environment, it suggests.

There are also landscape concerns – especially among those who advocate rewilding. Environmentalist George Monbiot argues that livestock production has a negative effect on the British landscape. The uplands have been “ravaged” by sheep production, he says, supporting a far poorer diversity of flora and fauna compared to what they did before man’s intervention.

Globally, rising demand for meat is also the catalyst for rainforest destruction, say the critics, as large swathes of land are cleared to make way for soya cultivation to provide the protein crops necessary to feed the world’s expanding herds and flocks.

The water impacts of rising global meat production are another concern, especially the large volumes used to cultivate crops for livestock feed.

“On a broad level, you can say that eating substantial amounts of meat is bad for the environment,” says Tim Key from Oxford University.

What the meat industry says

While animals do indeed produce a significant quantity of methane, the green pasture they graze on is a natural producer of oxygen and an absorber of carbon dioxide, so it also makes a contribution to mitigating climate change.

Tenant Farmers’ Association chief executive George Dunn says: “Agriculture is also a store of carbon, with the 10m hectares of grassland across the UK storing something like 600m tonnes of carbon, estimated to cover about one third of the UK’s ‘below ground’ carbon stock.

“This grassland is also responsible for the sequestration of about 2.4m tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent annually. Livestock farmers deserve our support, not our criticism.”

New methods of assessing the impact of methane – one of the most potent greenhouse gasses – also suggest it has a far lesser impact on actual global warming than previously thought.

“Long-lived pollutants, like carbon dioxide, persist in the atmosphere, building up over centuries,” says Michelle Cain from the Oxford Martin Programme on climate pollutants. “The carbon dioxide created by burning coal in the 18th century is still affecting the climate today.

“But short-lived pollutants, like methane, disappear within a few years. Their effect on the climate is important, but very different from that of carbon dioxide: yet current policies treat them all as ‘equivalent’”.

According to Myles Allen from the Oxford Martin Programme, who led this ground-breaking research in 2018, “we don’t actually need to give up eating meat to stabilise global temperatures. We just need to stop increasing our collective meat consumption. But we do need to give up dumping carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.”

It’s not all about climate change either. Many advocates of livestock farming point out that the iconic landscapes of areas such as the Lake District, Snowdonia or Dartmoor owe much to the influence of man and his livestock. Without it, they would revert to scrub and forest.

National Sheep Association chief executive Phil Stocker also points out putting sheep back into arable rotations in the lowlands would result in natural regeneration of soil quality and fertility, while grazing them on more diverse ley mixtures would help support invertebrates and pollinators.

Animal welfare

© Tim Scrivener

What the vegan/vegetarian lobby says

Both meat and dairy production are inherently cruel – especially factory farming where animals are reared in sheds and never see any natural daylight, it is claimed.

The anti-meat lobby also points to the pressure farm animals are put under to achieve high growth rates, the barren housing they live in and the excessive use of antibiotics to deal with the inevitable disease problems.

There are particular issues with dairy farming, where calves are “torn away from their mothers at birth” and male calves, which have no future as milk producers, are routinely shot. Breeding programmes also focus on maximising yield, meaning cows have unnaturally large udders and are prone to lameness and mastitis.

Pig production involves containing sows in farrowing crates, in which they are unable to turn around, for up to four months at a time. The sector is also criticised for the continued practice of tail-docking piglets.

There are plenty of claims about malpractice in the poultry sector, too. Broilers are kept in heavily stocked sheds with birds bred for unnaturally fast breast growth, which compromises welfare.

The egg sector is also blighted by welfare problems, say the vegans. So-called “enriched” cages may provide birds with opportunities to scratch and perch, but there is no access to natural daylight and stocking rates are still too high.

Free-range systems are better, though chicks still have their beaks “tipped” to reduce incidents of aggressive pecking.

The animal welfare lobby also complains that day-old male chicks are gassed as they have no use as future egg layers.

They also point to “meat alternatives”, such as Quorn or veggie-burgers, and lab-grown meat, which is set to become cheaper and can satisfy consumers without compromising animal welfare.

What the meat and dairy sectors say

The meat sector disputes many of these claims, especially that indoor production systems necessarily compromise animal welfare, or that breeding programmes are all about yield.

For many animals, group living is a positive, even indoors. Free-range systems of livestock production often expose the animals in question to higher levels of disease and, in the case of poultry, greater levels of aggression.

Conversely, housing livestock can lead to better disease management and, at times of inclement weather, a more comfortable living environment.

Five freedoms for animal welfare

- Freedom from hunger, thirst and malnutrition

- Freedom from pain, injury and disease

- Freedom from discomfort

- Freedom from fear and distress

- Freedom to express natural behaviour

Maintaining high welfare is also good for productivity.

The fact is, the vast majority of farmers care for their animals out of a sense of responsibility, but the economic consequences of letting welfare standards slip is another consideration.

With regards to male dairy calves, it is untrue to say they are routinely destroyed – an increasing number are reared for beef and others go for rose veal, being given a good life in group-housed, straw-bedded systems until they are ready for slaughter at about eight months of age.

See also: Poultry sector accuses George Monbiot of ignorance and ‘guesswork’

Male chicks from the egg sector are not a waste product either. They are used primarily for pet food, providing a nutrition source for snakes and raptors.

The UK is actually a net importer of frozen chicks, as domestic supply does not meet demand.

The ethical arguments for lab-grown meat as an alternative to real meat are also spurious, as producing it still requires the production and slaughter of live animals.

Current techniques involve the use of growth-inducing proteins, harvested from the live foetuses of in-calf cows, taken at slaughter and then grown in a culture with other nutrients.

Antibiotics

What the vegan/vegetarian lobby says

The anti-meat lobby makes strong claims about the excessive use of antibiotics in livestock production – especially prophylactic use – which, they say, encourage antibiotic resistant bacteria to develop.

Eating meat can then lead to a transfer of those bacteria, which contribute to anti-microbial resistance in humans, who are then more susceptible to bacterial attack, they argue.

What the meat sector says

In terms of antibiotics use, the UK livestock industry is making huge strides to reduce levels of use.

The poultry sector has led the way with an 82% reduction in antibiotics use in the past six years, while the pig sector, the largest user of on-farm antibiotics, has halved its use over the past two years.

Some use of antibiotics is, of course, essential to prevent animal suffering from diseases such as foot-rot, pneumonia and mastitis. But most farmers adhere to strict protocols, as set out by the Responsible Use of Medicines in Agriculture group.

Antibiotics have been banned as a growth promoter in livestock production for many years, and the rate of use on UK farms is far lower than overseas – in the US, for example, livestock farmers use twice as much antibiotics per kilo of meat.

The main cause of anti-microbial resistance to antibiotics in humans is the over-prescription of these drugs by doctors, and the tendency of humans not to finish the entire course.