How a grower slashed insecticide use by splitting fields

© FLPA/Bob/Gibbons-Shutterstock

© FLPA/Bob/Gibbons-Shutterstock A Cambridgeshire grower is reaping the rewards of encouraging beneficial insects, having eliminated the need to use any slug pellets or insecticides in his cropping system for more than a decade.

Tim Scott achieved this by developing a cropping system that provides habitat for wildlife at all times of the year.

There are three key parts to his unique approach – the bold move of splitting fields with hedges, practising “mosaic” farming to create a patchwork of fields with different crops, and overwintering stubbles.

See also: T0 fungicide advice for disease in late-drilled winter wheat

This approach means he has been successfully encouraging beneficial wildlife further into fields for decades, something a number of research projects – such as the Assist trials – have only just started to investigate.

His journey started in 1993, when he took on a tenancy with the Countryside Restoration Trust. His remit was to encourage as much wildlife on his farm as possible, while still being profitable.

The main focus of the trust has been on increasing bird and butterfly numbers, but to do so, he has had to provide the right habitat and food sources for the invertebrates which make up their diet.

These are the same insects that increase pollination of crops or provide natural pest control.

Although the measures he has introduced have been successful, they do increase the complexity of his farming operations, and require careful management.

However, potentially as a result of his environmental approach, Mr Scott hasn’t needed to use slug pellets in a decade or insecticides in nearly 15 years.

Tim Scott

Splitting fields

Mr Scott owns some of his 290ha cropping area, and also has numerous landlords, one of which is the Countryside Restoration Trust.

As the farmer of the land, Mr Scott has been tasked with reintroducing the four key resources needed by wildlife to live; somewhere to sleep, drink, feed and be free from disturbance.

The trust monitors butterflies, bees and birds across the farm, with their numbers presented at a results day each year.

But Mr Scott is also a tenant, and must farm in a profitable fashion in order to pay his rent.

“I pay a rent, but not the full market value,” he says. “That’s the compromise. If I have smaller fields and more varied cropping to support wildlife, this has to be reflected in the rent.”

His strategy revolves around the idea of creating wildlife corridors across his farm, and a major element of this has been replanting hedges.

Mr Scott has subdivided his 8ha fields by planting hedgerows that contain up to 14 different species to provide as much varied habitat as possible.

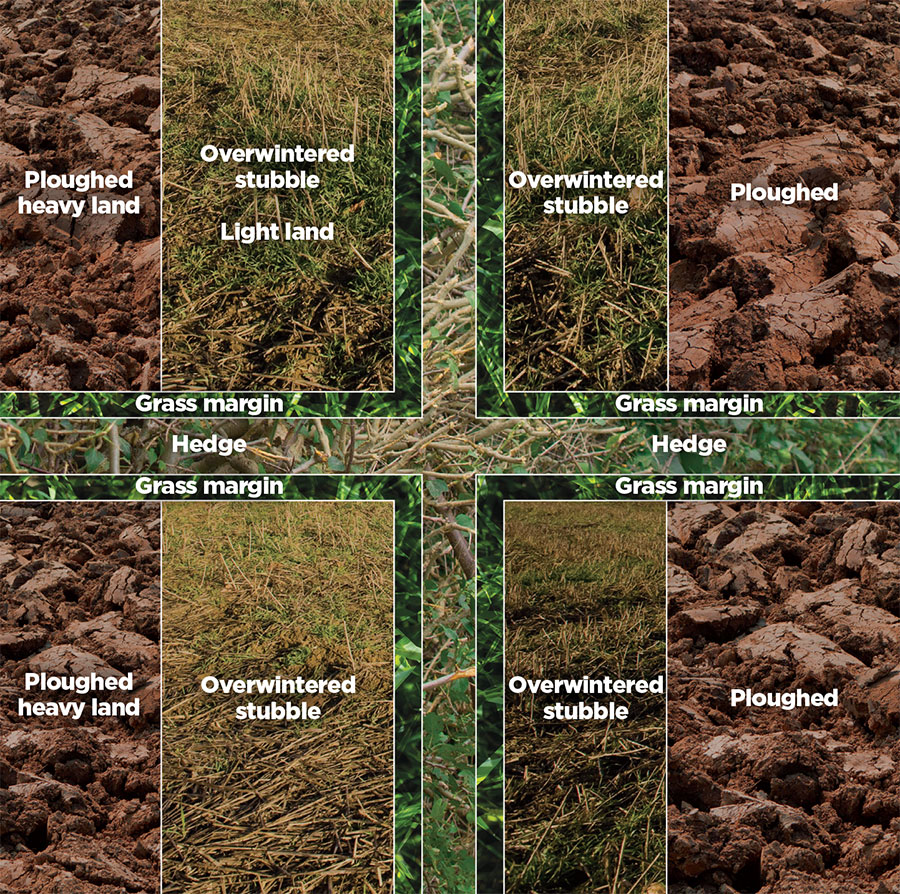

Fields have been divided with new hedges banked by grass margins

“You can always gauge the age of the hedge by the species within it – a lot of recently planted hedges only contain hawthorn.”

These hedgerows are then bordered with grass margins to provide habitat year round.

Mr Scott also cuts his hedges on a rotational basis, ensuring there is habitat left on the other side when cutting.

This is partly due to a lack of capacity, but also to ensure the habitat he has taken the time to create is not destroyed in the pursuit of a tidy farm.

“Many farmers have grass margins because they are in environmental schemes, but most farmers are also obsessed with hygiene.

“They combine the field, flail the margin and banks, cut the hedge, and then all of the habitat has disappeared. The way we manage our grass margins is critical.”

What about direct drilling?

Many people would assume that, as an environmental farmer, Tim Scott would be direct drilling. However, he says he has yet to be convinced that heavy land will restructure itself.

“I’m open-minded to direct drilling. It was very popular 30-40 years ago, but then it died out for a whole host of reasons.

“I still believe that when heavy soil slumps, it ends up really tight. But I can see the benefits of direct drilling in the winter and I’m considering doing some.”

Key elements of Tim Scott’s approach

- Hedge management Mr Scott has divided larger fields into four by planting hedges containing multiple species. These are banked by grass verges and cut on a rotational basis.

- Mosaic cropping Crops are not planted in blocks, so all the fields surrounding one planted with winter wheat will be drilled with a different crop.

- Overwintered stubbles Weeds and volunteers are left over winter on the lighter areas of fields to act as a free cover crop, heavy areas are ploughed.

Mosaic cropping

Rather than growing his crops in blocks – which would force ground-nesting birds to travel several fields away to find food, depending on the crop being grown that season – Mr Scott practises mosaic cropping.

This means he does not grow multiple fields of the same crop in one location (block-cropping), choosing instead to drill just a single field of one of the seven or eight crops within his rotation, with a different crop in each of the neighbouring fields.

This means some of his nesting birds can raise three clutches of eggs a season, rather than one, due to a reduced risk of predation while the parents are away hunting.

However, this also results in more complex logistics, a higher diesel bill and a longer harvest period for Mr Scott.

Harvest takes about a week longer than it would if he block cropped, and Mr Scott has 31 fields to drill this spring after this 70% winter and 30% spring cropping ratio was reversed by the poor autumn this season.

“I can’t say I’m not worried, because I am, but I am sure we will get there,” he says.

One of the main drivers behind Mr Scott’s use of spring cropping is blackgrass control, but he also grows spring crops for their benefit to the environment.

“In a spring crop, a pair of skylarks will have three broods of chicks, rather than one, due to an abundance of food, producing 12 chicks.”

Overwintered stubble

The third part of Mr Scott’s approach is having overwintered stubbles in place of cover crops, relying on leftover grain, volunteers and native weeds to provide wildlife habitat.

“My stubble fields have their own cover crops through volunteers,” he says, citing his heavy soil type as one of the main issues with drilled cover crops.

“I can’t see any great benefit from drilling cover crops, and they hold lots of moisture in the soil.

“If I did it on my lighter land, it might be beneficial.”

Mr Scott has evidence that his overwintered stubbles are providing for wildlife, as he has 110 bird feeders around the farm, which take a week to empty.

However, once he has ploughed his overwintered stubbles in the spring, they will empty in a day.

About 20ha of the overwintered stubble is in stewardship, which means he cannot plough it until 14 February each year.

Another 80ha left across the farm is not subsidised, allowing Mr Scott to plough any time from Christmas to spread out the workload and allow his soils to dry out before drilling.

In order to make overwintered stubbles work on his heavy boulder clay, he sub-divides his fields even further, leaving stubble in the lighter areas and ploughing the heavier soils.

He tries to plan out a stubble corridor which links up all across his farm, although admits this isn’t always possible.